To steal a line from the Toy Dolls c1983… “Trump, Trump, Trump”.

As most of us already realise, the world is bonkers; however, the fundamentals of investment have not changed in centuries.

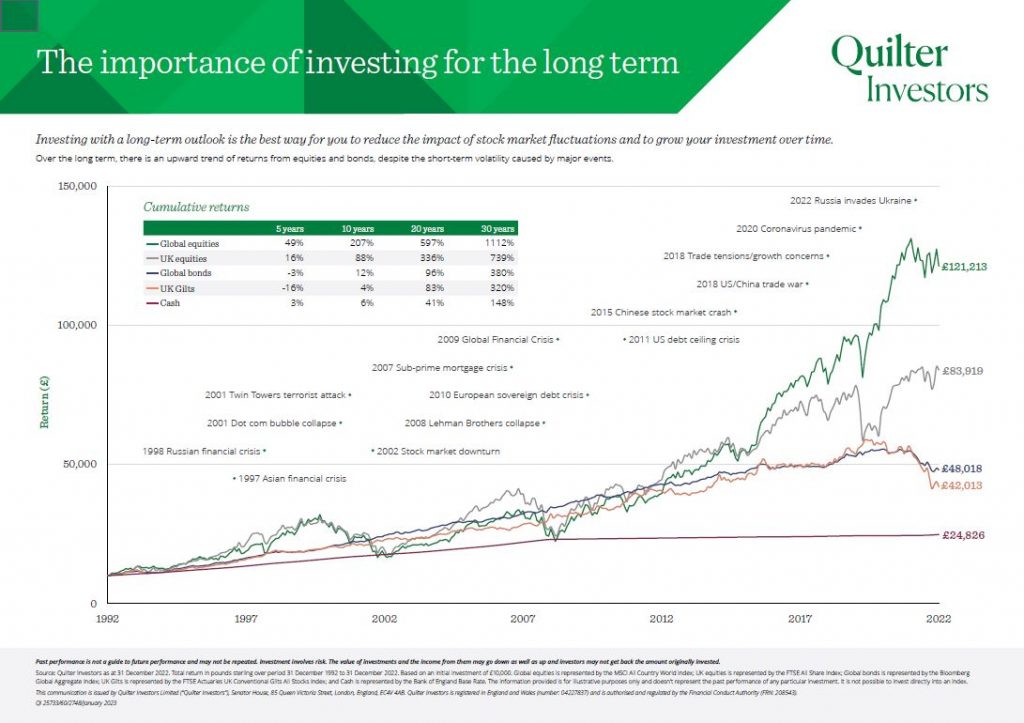

Global market volatility has been rising over the years as more ‘shorting’ of assets takes place, and more automated trading systems are put in place.

The recent ‘Trump Slump’ (or insert your own derogatory phrase) is only expected to be relatively short-lived.

The majority of asset classes and major markets were not over valued (based on 30 year averages) at the start of this debacle, hence the expectation that recovery should be fairly swift.

No one can predict the future, but one thing is for certain, the global investment markets have always previously recovered when a bump in the road has come along (world wars, dotcom crash, crash of 2008/9, terrorist acts, global pandemics etc. etc.).

So, to steal another line, this time from Lance Corporal Jones…“Don’t panic Mr Mainwaring”.

If you don’t need to disinvest, don’t. The most common mistake made by private investors is buying high and selling low, the complete opposite of the professional investor.

If you’re over-exposed to cash, then now may be a good opportunity to invest?

Ultimately, none of us know what’s around the corner, but I as I’ve already said, the fundamentals of investment haven’t changed in centuries.

As ever, please talk to your financial adviser – it’s what we’re here for!

David

David Hinch is the Managing Director of David Burnell Financial Services.